- Front Page

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Obituary

- Lisburn Bus Services In The 1920S & 30s

- A Glimpse Of Drumbeg, 1750-1800

- The Lisburn Area in The Early Christian Period.

- Childhood Memories Of Mona Mckeown(1904-985) Of Glenavy

- Bishop Jeremy Taylor's Funeral Hatchment

- Black Abbey, The Archbishops Of Armagh And The Church Of Derryaghy

- Edward Smyth, M. P. For Lisburn 1740-60: His Token

- The Establishment And Early Day Of Technical Education In Lisburn, 1901-1920

- Bygone Days

- The Arrival Of Paddy The Piper, By Samuel Mccloy:

- Book Reviews

- Historical Journals

BYGONE DAYS

(Extracts from assorted newspapers, compiled with accompanying notes by Eileen Black).

JAMES DARBY'S WRITING SCHOOL, 1768.

Just arrived in Lisburn, James Darby, Writing-Master, who

has opened School in this Town; where Youth may be taught in the Art of Writing

from the Age of 6 to 40 Years to write in all the Hands used in Great Britain

applicable to Business in Three Months. No Purchase no Pay. Such Gentlemen and

Ladies as are desirous to have their Families taught at their Houses, may be

assured that in 24 Hours they shall write a free natural Hand, in Failure of

which the Rates agreed on are forfeited. Price in my publick School, half a

Guinea a Month, and a Crown at Entering. Private Teachings a Guinea a Month, and

Half a Guinea at Entering.

N.B. Such as are desirous to learn to print the Italian Hand, German Text, Bastard 'Text, the Engrossing Set Hands, and all the mixt and running Secretaries, with the Court and Chancery Hands (with many others too tedious to mention) are taught in the newest Method, with great Variety and natural Freedom...

Belfast News-Letter, 1 July 1768.

EXHIBITION OF The MICROCOSM, 1777.

That inimitable Piece of Art called the Microcosm, is arrived, and will be opened for the Inspection of the Curious, in the Market-House, on Monday next, the 22nd, and to continue there until Tuesday evening the 31st Instant, positively no longer. To begin every Day at the Hours of twelve and seven o'clock. Admittance at One English Shilling each. Those Ladies or Gentlemen who chose to subscribe five British Shillings each, will be entitled to see the Microcosm, as often as they please, during its Stay.

N.B. Of the Proprietor may be had, Price 6d, h. a succinct Description of the Microcosm, also, a large Copper-plate Print of the same, Price 2s 2d. The Proprietor repairs and tunes Barrel Organs, Harpsichords, and Spinets in the correctest Manner.

Belfast News-Letter, 19 April 1777.

[This exhibition was touring around the North in 1771, and had already been shown in Londonderry and Coleraine. After Lisburn, it moved to Belfast in early May and remained there until 21 June. It is not known what this `piece of art' actually was. It may perhaps have been illustrations showing the workings of the universe].

MR. HART'S DANCING SCHOOL, 1775.

Mr. Hart will open School in the Market House in Lisburn, on Monday the 8th Day of May inst., and in the Market House in Lurgan, on Thursday the 11th, at Half a Guinea a Quarter, and Half a Guinea Entrance. He hopes that his having acquitted himself to the Satisfaction of those who have lately employed him, will Recommend him to those who may now have Occasion to do so.

Belfast News-Letter, 2-5 May 1775.

[John Hart had formerly been in partnership with Richard

Lee, a dancing master who ran a school in the Market House in 1773. The

partnership was dissolved in 1774 and Lee moved to Belfast, to open a school in

the Market House there].

![]()

SIGNOR BARLETTE'S MUSIC LESSONS, 7777.

Signor Barlette takes this Opportunity to acquaint the Gentlemen and Ladies of Lisburn, that he will be there on Monday the 19th instl., to teach Ladies the Guitar, and Gentlemen the Violin: He accompanies the Harpsichord with the Violin: He teaches Singing in the newest Taste.

Those Gentlemen and Ladies that will honour him with their Commands, will please to observe his Stay in Lisburn will be from Mondays to Wednesdays; the Remainder of the Week in Belfast: His Terms are three Crowns Entrance and three Crowns a Month.

N.B. Please to enquire for him at Mr. Hastings, Bear, Lisburn.

Belfast News-Letter, 14-16 May 1777.

[The Bear was a local inn].

GLASS EXHIBITION IN THE MARKET HOUSE, 1777.

H. and D. Ayckbourn, From London and Dublin, have now for Sale, in the Assembly-Room, over the Market-House, Lisburn; A Large and elegant Assortment of the best cut, engraved, and plain London Flint Glass, consisting of Girandoles [candelabrum], Hall and Stair-Case Bells, Candlesticks, Decanters, Drinking-glasses, and every other Article usually made of Flint Glass. They flatter themselves the Collection will be found much superior to any ever seen here; and as their Prices and Manner of Dealing have secured them publick Favour in most other Parts of the Kingdom, they hope it will also recommend them to the Inhabitants of Lisburn.

N.B. They ask but one Price, and will positively leave Town the 15th of June.

Belfast News-Letter, 10.13 .June 1777.

[The above extracts show eighteenth century Lisburn to have been well acquainted with the finer things of life: music, dancing, fine handwriting skills and education. The Market House was certainly the hub of the town's social scene, for apart from the various balls held there, it acted as an exhibition center for numerous passing shows and was home to various dancing schools, like Lee's and Hart's.]

BULLET MATCH AT BALLYLESSON-SPECTATOR GOES MISSING, 1872.

On Saturday evening last, a challenge bullet-match, on the public road, between Ballylesson Church and "Gardiner's Lane Ends;" not very far removed from the good town of Belfast, and certainly not beyond the pale of police supervision, occasioned a concourse of some two thousand spectators, many of whom came from a distance-betting men on a small scale, excitedly interested in the issue of the match, and others attracted to the place merely by the spirit and love of idle curiosity. Amongst the latter was a man named Hutchinson, who was in the employment of Mr. Crommelyn Irwin, of Newgrove, for five or six and twenty years; and he, after the match was decided, having imbibed rather too freely of the cup that cheers but yet inebriates, started from the "Lane Ends" for his home (Mr. Irwin's porter-lodge- about half past eleven o'clock p.m. That home he never reached, and he has not since been heard of, though search has been made for him in all directions round. It is the general belief that he must have wandered off the road, and have fallen into the Lagan which runs near, but no trace of him has yet been discovered, and his fate still remains a mystery. He was alone, and was very much the worse of drink when last seen. He leaves a wife but no family, and she poor woman, as may well be supposed, is in a state of mind bordering on distraction at his untimely loss, or rather his strange and mysterious disappearance. 'that he is dead there can be scarcely any doubt, but where can his body be? The river and all the water near the road have been dragged, but all to no purpose. It may (and to most people in the neighbourhood certainly does) seem strange that though the Royal Irish [the police, then called the Royal Irish Constabulary] are represented at no great distance off, and though there are several magistrates in the vicinity, such an affair as a challenge bullet-match, which attracted such numbers to witness it and which must consequently have been well ventilated [publicized] before it came off, should have been permitted on the Queen's highway, to the great danger, inconvenience, and annoyance of all resident near the scene of the "sport", and to all persons legitimately using that road; and it is also somewhat singular that, though crowds were drinking at a public-house in the "Lane Ends" for hours after the match was played, the face of a policeman was not seen on the road that evening. In fact, the R.I.C. were "conspicuous by their absence" from beginning to end of the affair.

Northern Whig, 18 May 1872.

The unfortunate man's body was fished out of the Lagan,

near Drum Bridge, on 24 May following. 'Gardiner's Lane Ends' was in fact Gardners Loan Ends, where nowadays, the Drumbeg Road meets the Ballylesson and

Hillhall Roads, at the Homestead Inn. Newgrove, Mr. Irwin's demesne, was on the

left hand side of the road, heading from the Loan Ends to Drumbo Parish Church,

and about three quarters of a mile past Belvidere. Bullet matches were a

frequent occurrence around Lisburn, Ballynahinch and Saintfield at this time, to

the disapproval of numerous local residents, who accused the R.I.C. of turning a

blind eye to the sport. For brief details of bullet throwing, see this Journal,

vol. 6, Winter 1981-1987, p. 58].

![]()

MILL WORKER'S EXCURSION TO ANTRIM, 1873.

On Saturday last, the employees of the firm of Messrs. Robert Stewart & Sons, Flax Spinners and Thread Manufacturers, Lisburn, numbering about 700, had an excursion to Massereene Park. The procession, headed by a beautiful banner (painted by Thomas Robinson, one of the employees, with the name of the firm and view of the mill on one side, and "Success to the Linen Trade", inscribed in gold letters on the other), followed by the Lisburn Amateur Brass Band playing lively tunes, left the mill at half past nine o'clock, and marched in good order through the principal streets, each department carrying handsome banners, to the railway station, where a special train was in readiness to convey them to Antrim. On arrival at Antrim, all got into order and marched for the park, the use of which was kindly granted by the agent, C. K. Cordner, Esq. The weather being all that could be desired added much to the enjoyment of those present. After a sumptious repast had been partaken of, amusements of different kinds were heartily entered on. The utmost good order and humour prevailed. After a second distribution of refreshments, a vote of thanks was proposed by Mr. Frazer, seconded by Mr. Dorman. and carried by acclamation, to Messrs. R. Stewart & Sons, Sir Richard Wallace, Bart., M. P; Mr. Savage, the manager of Messrs. Stewart's mill. Mr. Savage, on returning thanks for the compliment, referred to the kindness and generosity of Messrs. Stewart in subscribing so liberally towards the expenses incurred, and to the great interest they always take in the welfare of their workers, and also to the generosity of Sir Richard Wallace, who, on a recent visit to the establishment, placed a sum of money in his hands for the benefit of the workers. On returning to the railway station in the evening, Mr. Savage was chaired from the Park through the streets of Antrim to the Castle, where the whole party gave three cheers for Sir Richard Wallace, Lady Wallace and Captain Wallace. On approaching the station at Antrim, Sir Richard passed the procession, accompanied by Captain Wallace and Mr, Capron, who received and courteously acknowledged the plaudits of the people. The party reached Lisburn about half-past seven o'clock, all highly delighted.

Northern Whig, 16 September 1873.

[During the second half of the nineteenth century and the earlier years of the twentieth, excursions such as this were often the highlight of the year for factory workers, clubs of various kinds, Sunday School groups and school children. On such outings, processions were usually accompanied by banners and bands and a certain formality observed until reaching the destination].

LISBURN TEMPERANCE UNION ANNUAL MEETING, 1909.

The annual meeting of the above Union was held on Saturday evening [3 April] in the Temperance Institute in the presence of a large assembly ... The annual report was presented ... and was as follows:- "In presenting the twenty-second annual report of the Lisburn Temperance Union the Committee feel that, while there is nothing of an extraordinary kind to set forth, there is yet ample ground for thankfulness that some good work has been done during the year, and some unmistakable testimony borne in the interests of temperance. Early last summer an interesting and instructive card showing the evil effects of alcohol was distributed through all the homes in the town ... The idea of producing and distributing such a card was suggested by the late Mrs. Stears, a very sincere friend of every good cause. The card, which is adapted for hanging up in the home, is well calculated to be of much educative value; and education in the evil effects of alcohol on body, brain, and soul, in homes, in business, and in the national fife, is one of our greatest needs ... Two series of public meetings were held during the year. One of these was in the open air last July [July 1908], when admirable addresses were delivered on five successive evenings by Mr. London Ward and other friends from the Irish Temperance League. The other aeries of meetings was held in the opening days of the new year in the Orange Hall, when stimulating and excellent addresses were delivered by Revs. A. F. Moody, C. C. Manning, J. Macmillan and Mr. Ward ... When we come to the life and work of this Institute during the year we find that the Cafe, under the able management of Miss Dickey, is as popular as ever ... All the rooms were well patronised, and the Treasurer's statement shows a healthy financial condition, were it not for the heavy interest that has to be paid on the large debt - the debt incurred by the extension of the premises two years ago. While this Institute may not be fulfilling all the ideals and expectations of its friends, as it might be, yet if by some calamitous stroke it were swept out of the town there would be a great blank and much lamentation in the interests of many good and useful causes, and the Committee are thankful that on the broad bases of temperance, free from all sectarian or party strife, all can find here in the reading, recreation, and other rooms a welcome and a fitting meeting-place away from the snares and temptations of the public-house.

The Committee have one other matter to report. The late Miss Brownlee had a warm regard for this Institute and a very great interest in the highest wellbeing of her native town, and by her will she left £500 for the founding of a library in this Institute and £15 a year for the supplying of new books, on condition that the trustees provide adequate accommodation for it. This would meet a much-felt want in our midst. It is not creditable to our town and scarcely worthy of the enlightenment and public spirit of our city fathers that, while Banbridge, Lurgan and Portadown have their libraries and technical schools, Lisburn, the most prosperous of them all, has none of these advantages. In this generous bequest of Miss Brownlee the case may be partially met. But what are the trustees to do? - There is already a debt of £765. They feel they cannot add to that debt, they must diminish it. They cannot spend more money till some way of clearing off the old debt emerges. They are seriously considering the matter. Perhaps someone who hears this report can help them to solve the difficulty." The report was unanimously adopted, and the proceedings shortly afterwards terminated.

Northern Whig, 5 April 1909.

[Lisburn Temperance Union was founded in 1887 and the

Temperance Institute erected during 1889-90. The Union's first President was

James Nicholson Richardson of Lissue and the first Honorary Secretary was Rev.

R. W. Hamilton, of Railway Street Presbyterian Church. The Temperance Union is

still in existence and holds regular meetings in the Institute. The building

itself, however, was sold to Lisburn Borough Council in 1979 and thereafter

became part of the Borough's community services. It is now known as the Bridge

Centre. The Brownlee Library did materialize, in fact, being officially opened

on 21 September 1910, in the presence of Mr. Elliott, Chief Librarian of Belfast

Free Library. Note the `dig' about Lisburn's lack of a technical school, in

comparison with less populated towns like Banbridge and Lurgan, which already

had such facilities. See McReynolds' article in this Journal for an interesting

account of this particular issue].

![]()

THE ARRIVAL OF PADDY THE PIPER, BY SAMUEL MCCLOY:

AN IMPORTANT NEW ACQUISITION FOR LISBURN MUSEUM.

|

| Samuel McCloy, The Arrival of

Paddy the Piper, oil on canvas 71.1 x 96.5 cms, collection Lisburn Museum. |

BRIAN MACKEY

The Arrival of Phadrig no pib (Paddy the Piper), painted in 1873 and exhibited at the Royal Society of British Artists, London, in the same year, is a major work by Samuel McCloy and an important new acquisition for Lisburn Museum.1 McCloy was born in Bridge Street in 1831 and is without doubt Lisburn's most notable painter. 2 He has only recently emerged from the shadows, though he was very popular during his lifetime and highly prolific, particularly in watercolour. In his later years according to family tradition, his London agent in Duke Street sold his work to visitors from North America as quickly as he cold turn it out.3 Many paintings were also sold through other London galleries. McCloy's move from Belfast to the capital in 1884 undoubtedly encouraged this trade. Six of his watercolours were acquired by Sir Richard Wallace, one of them being exhibited in 1876 at the Industrial Exhibition in Belfast's Ulster Hall4 It may be assumed that Wallace, a great connoisseur of European painting, valued them for their quality and was not simply patronizing an artist from his Irish estate.

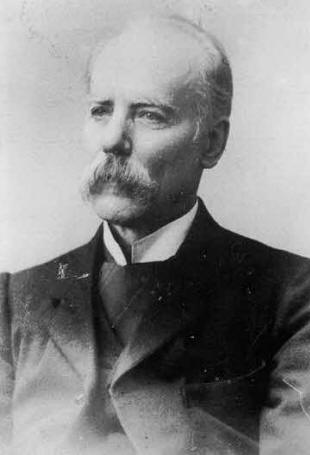

|

| Samuel McCloy (1831-1904), Lisburn's most notable painter. His work has become highly valued in recent years. (Photograph courtesy of the McCloy family). |

The Arrival of Paddy the Piper proves, as it were, McCloy's abilities to work with a much larger subject than usual, and shows how fine and competent he was with oil. The painting contains about thirty figures of various ages, confidently arranged in an Irish folk incident of great charm. It is a delightfully happy picture, with enthusiastic children and adults surrounding the piper, on his arrival at their village. It is undoubtedly a major and quite exceptional work by McCloy, which must encourage a revision of his status. As Professor Anne Crookshank said at the reception to mark the painting's acquisition `... he is not a minor Irish artist now'.

McCloy's work is represented in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, the National Museum of Wales, the National Gallery of Ireland and the Ulster Museum. Lisburn Museum is indebted to the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the National Art-Collections Fund, through the Eugene Cremetti Fund, for generously helping to acquire this important example for its collection.

References

| 1. | Purchased in March, 1988 from Pym's Gallery, London. See exhibition catalogue, Irish Renaissance, Pym's Gallery, 1986, pp. 14-15. |

| 2. | For biographical details, see Eileen Black, Samuel McCloy 1831-1904 Subject and Landscape Painter, exhibition catalogue, Lisburn Museum, December 1981 - February 1982. |

| 3. | By Samuel McCloy, the artist's grandson. |

| 4. | The location of these watercolours is unknown; they are not in the Wallace Collection, London. |

| 5. | Anne Crookshank and The Knight of Glin, The Painters of Ireland c. 1660-1970, 1978, p. 225. |

| 6. | McCloy catalogue, op. cit all sixteen were donated to the Ulster Museum by William Corran, in 1954. |

| 7. | Ibid; p. 13. |

| 8. | Ibid; illustrated p. 17. |

BOOK REVIEWS

J. R. R. Adams,

THE PRINTED WORD AND THE COMMON MAN: POPULAR CULTURE IN ULSTER 1700-1900,

Belfast: Institute of Irish Studies, 1987, £12.50.

Although there has been a great deal of excellent research and publication on Irish bibliography, until this present volume there has been no extensive examination of the history and influence of so-called `popular literature' in Ireland. Adams is to be praised for undertaking an initiation of research into this field through a thoughtful and obviously painstakingly researched examination of the genre, in Ulster, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Popular literature in Ulster is covered in chronological order. The author interweaves histories of literacy, book publishing, printing, and selling, with an examination of the texts, in an attempt to produce a comprehensive picture of not just the scope of material available in this particular period, but also of its relationship to its society. For Adams believes that 'popular reading habits ... can form a reliable mirror in which we can see the mind of past generations at work and play,' (p. 6)- a commonly held assumption, but one which needs to be carefully qualified, in that no genre of literature, or any other form of social expression, can wholly mirror any society. An examination of popular reading habits may reveal something of popular aesthetics, beliefs and attitudes, or of the literary influences abroad at given times, but it cannot claim to do much more.

After a very clearly written Introduction setting out some of the background to the ensuing discussion, the opening chapter traces the development of education and literacy in Ulster in the eighteenth century, showing how this did not rest solely with the hedge-schools, but also, especially towards the end of the century, on church-controlled education (e.g. Sunday schools).

In his discussion of the distribution of popular literature in the eighteenth century. Adams is right to stress the importance of the Chapman. This itinerant peddlar played a vital role in the dissemination of many forms of popular literature, (garland, chapbook and broadside) from the centres of production to the far-flung reading public.

The following three chapters discuss the great variety of material to be found in the chapbooks religious and traditional secular material, children's literature, fiction, non-fiction and songs. This vast array, from the works of nonconformist authors to Pilgrim's Progress, from the New history of the Trojan wars and Troy's destruction to the dubious sexological Works of Aristotle, from Burns' Poems, chiefly in the Scottish dialect to the United Irishmen songs of Paddy's Resource, is presented to the reader with excellent exemplification and description.

The second half of the book, dealing with the nineteenth century, takes much the same pattern, starting with an examination of developments in education and literacy. Adams shows that even before the Education Act of 1830, a great wave of progress had begun through the work of the Sunday School system and various philanthropic societies, in particular, the Kildare Place Society.

In the nineteenth century, the importance of the Chapman as the dominant means of distribution declined with growth of retail outlets and the emergence of circulating libraries, though the latter were initially beyond the means of the less well-off.

This century saw a virtual monopoly on popular literature in Ulster held by the Belfast firms of Joseph Smyth and Simms & M'Intyre. Adams traces, with fascinating and extensive illustration, the development of popular literature from small-scale literary expressions of the local voice, to the mass productions designed for a more universal market governed by maximum commercial gain. Of particular interest in the history of mass readership was the innovative, and soon imitated, Simms & M'lntyre's Parlour Library, which from its Ulster birthplace emerged to change the whole concept of popular publishing in these islands.

There are two points of some contention in the book's

title. Firstly, there is the problem of definition for `the Common Man.' Time

and again in the book there are references to 'the common reader' (p. 43), `the

ordinary literate person' (p. 124), or `the lower orders' (p. 173), yet there

does not seem to have been a clear attempt to define who it was that Adams saw

as comprising the readers of popular literature during this period. While

acknowledging the difficulties involved in making such an identification,

especially in Ireland. I feel some attempt, however rudimentary or qualified,

might have been made. The other point in the title which I would query is its

claim to be an examination of 'Popular Culture in Ulster 1700-1900." While

popular literature is certainly a constituent part of popular culture and may

throw light on other parts of it, it cannot be claimed that the two equate

(indeed, the defination given by Adams in his introduction (p. 7) makes this

clear).

![]()

Whilst acknowledging the benefits of concentrating attention to a small area such as Ulster, it would have been beneficial had Adams placed the Ulster scene more in comparative perspective with the situation in the rest of Ireland and in Great Britain. The concentration on the nine counties undoubtedly gives depth, but surely the commercial links between Ulster and the rest of Ireland and with Britain must have had a notable influence on production, style and content. There are some other areas where further expansion would be advantageous- A description of the quality of production standards might address the legibility of the chapbooks (from personal research, I know that there were often problems of legibility with broadsides). Since there are no facsimile copies of the chapbooks available, fuller exemplification of the works themselves would give the reader a clearer appreciation of the various styles and language they employed (these could have formed an interesting and self Contained appendix).

Though the eight appendices are admirable because of the hitherto unpublished information that they make available to the reader and scholar, I am puzzled that there is not a clear listing of all extant works mentioned in the book, both of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Further, I am dismayed that the author has not seen fit to provide fellow scholars with details of relevant library holdings to facilitate further research in this and related fields.

These criticisms aside, this is an excellent study of an area which has been sadly neglected until now. The author has pulled together large amounts of material and has provided not just a valuable account of the wide range of material available in Ulster in these centuries, but also attempted to place this within its social and historical contexts. The Institute of Irish Studies must also be praised for facilitating the production of a book of such fine quality. This volume will almost certainly prove to be of great worth to social and literary historians and scholars of popular culture and folklore, and also to be of considerable interest to the general reader.

Colin Neilands (Dr.),

Queen's University, Belfast.

Philip Orr,

The Road to the Somme - Men of the Ulster Division Tell their Story,

Belfast: Blackstaff Press, 1987, £9.95.

Philip Orr an English teacher in Friends' School, Lisburn, has produced an historical study of lasting value for those who wish to understand Ulster in perhaps the major crisis of its modern history. He has achieved this, as his subtitle informs us, by allowing the few surviving veterans to tell their story in a moving and explicit account. He avoids a narrow focus by setting Ulster within a framework of early twentieth century Ireland and declares his aim is to `commemorate all Irishmen in a war they found so difficult to understand', though it must be admitted that to fulfil this intention, it would be necessary to produce a parallel volume on the Irish Volunteers.

This is a rare enough type of book. It is scholarly yet popular in appeal, with an excellent selection of photographs and delightful cartoon sketches by Jim Maultsaid. It is in straightforward language yet beautifully written in an orderly narrative style, which never ceases to hold interest and which carries the reader on to its awful tension-filled climax. One's only regret is that there was no Philip Orr to carry out the task twenty years earlier, when so many more participants would have been available for interview. The remarkable thing about the book, nevertheless, remains the fact that it has been researched at the very last opportunity, - and for this, and the highly impressive use made of the testimony of so few, the author deserves the greatest praise. One also has to admire the fair-minded way in which Orr handles material which has become part of a sectarian folk tradition, and which has been glamorized as a story of Ulster loyalists rushing to fight for King and Empire. He recognizes the confusion of loyalties out of which the Ulster Division took its being, with the U.V.F. not giving an unconditional loyalty to Britain but reluctantly accepting Carson's negotiated suspension of Home Rule. It is also pointed out that recruitment for war service was as strong in many Roman Catholic areas as it was in Protestant. Perhaps Orr expected too much of Carson, for in September 1914, when it was generally thought that the war would he `all over by Christmas', could Carson have been other than 'ignorant of how easily his men would became a much more disposable tool in a more lethal struggle, for imperial status and wealth in the modern world.'

What of the 36th (Ulster) Division's superhuman qualities and their exceptional, if short-lived breakthrough on the 1st July? Err argues that the Division's objectives were achieved because they set out info no man's land before their artillery had lifted the final barrage and were much closer to the German lines before being slaughtered by the machine gun crossfire. It is a plausible explanation but one unlikely to be popular with those who prefer a glorification of the Ulster Division's achievement at Thiepval. The book does not in anyway demean the bravery and determination of those who attacked on that day. but by allowing the ordinary soldiers to speak with their own 'mundane and authentic voice', it allows the wader to see the awful horror and futility of the Somme through a dignified and at times very moving, first-hand account.

The many illustrations are an important contribution to the purpose of the book. They give a poignant record of those who marched away, linking as they do the heady days of amateur soldiering to the desolation of the silent battlefield. The world charged irrevocably, in the years between the photograph of the Enniskillen Horse at the trot in 1914 and that of Thiepval after the Armistice.

In all, Philip Orr has succeeded with unobtrusive skill in telling an immensely human story. Indeed, it is perhaps regrettable that so enduring a monument to the contribution of the Ulster people to the Great War has not been produced in a hard back edition, for it is surely a book of lasting importance. It is authentic history, written in a remarkably convincing manner, with a felicity of style that could provoke envy in those not so gifted.

Brian Mackey, Lisburn Museum.