- Volume 10 Front Page

- Contents & Foreword

- New Life for an Egan Harp

- Memories of Glenmore House

- The Brontës & Arthur Bell Nicholls

- Jack Sinclair Local Hero

- Lisburn's Historic Quarter

- The Richard Wallace Trust (Lisburn)

- The effects of the Spanish Civil War on Ireland

- Hillsborough House Twelfth Night Ball

- The Blessington Estate And The Downshire Connection

- A Brief History Of Lisburn's Airbases

- Recollections Of The Second World War In Lisburn

- The end of an era - Barbour's Of Hilden

- Summer outings

2000 - 2005 - Recent Book Launches & Meetings

- Book Reviews

- Historical Journals

Lisburn Historical Society

Volume 10 • 2005 - 2006

LISBURN'S HISTORIC QUARTER

Lisburn Historic Quarter Partnership was established in 2000 and comprises key interests from the public, private and voluntary sectors. Its aim is to achieve physical, social and economic regeneration of the historic core of the city as it was first laid out in the early 17th century. The Partnership programme contains a number of subgroups which have developed initiatives relating to the built environment, the public realm, town centre living, economic investment and sustainable economic development. Bridge Street Townscape Initiative is one of these projects and an outline of its progress to date is provided by Alan Jeffers, Lisburn City Centre Manager.

Another aspect of the regeneration of the Historic Quarter is the planned restoration of Castle Gardens to create a safe and attractive public space for the whole of the community. There will be a sympathetic restoration of the design of the gardens and additional pedestrian access from Castle Street, Bridge Street and the River Lagan. The first stage of the restoration has commenced with archaeological excavations of Castle Gardens which took place in 2003.A report on these excavations is given by Ruairí Ó Baoill.

Staff of the Irish Linen Centre & Lisburn Museum have been closely involved in both projects, through the provision of historical research and advice on architectural matters in Bridge Street and historical research and the provision of an education and interpretation service for Phase I of the Castle Gardens Restoration Project. The Museum will continue to be involved through, for example, providing ongoing basic resources for Dr. Brian Turner's work on the 'Reminiscences of Bridge Street ' part of the Bridge Street Initiative, and through providing management of the education service to be associated with Phase II of the Castle Gardens Restoration Project in 2006-2007. The 'Castle Gardens Tours' of the archaeological excavations which have become a very successful feature of the Museum's activities have been greatly enhanced by the on-site assistance of Ruairí Ó Baoill and have been highly commended by the Heritage Lottery Fund as a model for others elsewhere to follow.

BRIDGE STREET REGENERATION IN ACTION

ALAN JEFFERS

The Bridge Street Townscape Heritage Initiative is a project managed by Lisburn City Centre Management with a budget of just over £2 million. It is one of several current Lisburn Historic Quarter projects taking place with the overall aim of increasing civic pride and city centre economic regeneration.

The project commenced in 2000 following a successful application by Lisburn City Centre Management to the Heritage Lottery Fund. This resulted in an award of £700,000 generously matched by Lisburn City Council, DoE Planning Service, the Down Lisburn Trust and the Northern Ireland Housing Executive.

A small partnership team was established with representatives from the Irish Linen Centre & Lisburn Museum, conservation experts Manor Architects, Lisburn City Council, Planning Service, Housing Executive and Lisburn City Centre Management. The restoration ethos of the team from the outset was to ensure that the 'quality and character' of the buildings were not compromised.

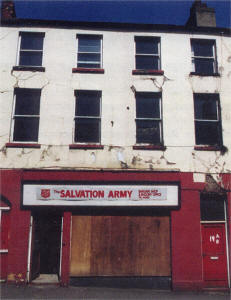

The heritage need was revealed in a survey conducted during 1999 which indicated that around 85 per cent of the buildings were in poor structural condition. Similarly the lack of vibrancy was reflected in the very high vacancy levels; 30 per cent at ground floor and 75 per cent on upper floors. Bridge Street's 52 individual properties required considerably more than simply a superficial facelift.

There have been 19 projects completed in Bridge Street involving 16 properties and attracting around £1,000,000 of additional private sector investment. These were mostly intensive 'rescuing a ruin' type projects although a minor contract to enhance the façade of one building was also undertaken. Many buildings have also experienced a change of use, for example in the provision of apartments above retail outlets. To date 12 new residences have been created and all are occupied. This 'Living Over The Shop' concept also makes a valuable contribution towards re-establishing Bridge Street's own community identity.

Therefore while very good progress has been made over the past five years, the overall objective towards achieving sustainable regeneration is far from complete. Current funds are simply insufficient.

To address this situation a second Heritage Lottery Fund application was submitted in 2004 for a further five year Townscape Heritage Initiative scheme with grant support of £955,000. The outcome will be known early in 2006. Lisburn City Council has already generously agreed to contribute £575,000 in matching funding, subject to further Heritage Lottery Fund support. Other sources of income will hopefully include the Planning Service, Northern Ireland Housing Executive, Department of Social

Development and the International Fund for Ireland. A further £2,000,000 remains to be secured from the private sector whose contribution is crucial to the achievement of a sustainable future for Bridge Street underpinned by the sympathetic regeneration of the existing historic built environment.

Around 2010 an Environmental Improvement Scheme will be implemented to address issues such as the upgrading of the footpaths and roadway together with appropriate street lighting and essential furniture. By 2011 it is envisaged that the Heritage Lottery Fund regeneration of Bridge Street will be complete.

Complementary to the physical regeneration, we are also addressing the social heritage aspects of Bridge Street through an initiative entitled 'Reminiscences of Bridge Street'. Again supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund with matching funding from Lisburn City Council through the Bridge Street THI, the aim of the project is to provide a brief history of Bridge Street together with the reminiscences of people who either lived or worked in Bridge Street during the 20th Century.

Dr Brian Turner, a well-known and highly respected figure in local history circles, has been commissioned to produce the 'Reminiscences' booklet and to develop an associated exhibition which it is anticipated will be on display in the Irish Linen Centre & Lisburn Museum in 2006. Brian would welcome all contributions to his research and can be contacted by email Brian@lisban.freeserve.co.uk.

For further information on any aspect of the

Bridge Street regeneration project please contact Alan Jeffers at 3a

Bridge Street. Lisburn BT28 1XZ, tel. 028 9266 0625 or

alanjeffers@lisburnccm.co.uk Photographs are the copyright of

Lisburn City Centre Development Ltd.

![]()

|

|

| 14 Bridge Street (before). A property constructed of stone rubble with render and its original box sash windows. | 14 Bridge Street (after). Newly restored and available for rent. |

|

|

| 19 Bridge Street (before). Ground floor shop with separate entrance to upper floors. | 19 Bridge Street (after). Replica of the golden lion from the Lion Tea House donated by Lisburn Historical Society to the Museum. |

EXCAVATIONS AT CASTLE GARDENS, LISBURN

RUAIRí Ó BAOILL

A licensed archaeological excavation was directed by the writer, on behalf of Archaeological Development Services Ltd, on the terraces of Lisburn Castle Gardens (Grid Ref: J 2694 6433; Excavation licence No.: AE/ 03/ 57; SMR Number: Antrim 68: 2). The investigation took place from 7 July-31 October 2003 and was part of an archaeological assessment of the potential buried historic garden remains that constitutes the first phase of a Heritage Lottery Fund and Lisburn City Council financed restoration of the whole gardens.

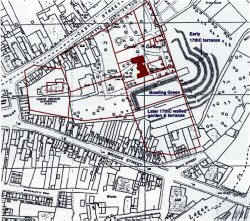

Lisburn, eight miles south-west of Belfast, was the centre of a plantation land grant to Sir Fulke Conway in the early 17th century. Castle Gardens were, in the 17th century, part of a large formal garden attached to a manor house (the Castle) which no longer exists. Layout was initiated by Conway, but substantially developed from the 1650s onwards by George Rawdon, the Conway family's agent in Ireland. The original gardens now cover a much-reduced area and currently constitute Castle Gardens Park. (Fig.1) The four terraces being archaeologically investigated were at the southern limits of this park. The investigation took the form of 16 manually excavated trenches on the terraces to look for presence or absence of garden features and to help inform the restoration of the various walls dividing each terrace (Fig. 2). No features or artefacts earlier than the 17th century were found.

The site of Lisburn Castle is located in the modern Castle Gardens, a public park in a prominent position on top of a hill which commands good views in all directions, particularly to the east over the River Lagan. As they currently survive, the gardens are divided into three distinct areas. The first of these is to the east and constitutes at least four curving terraces, now covered in grass, with mature trees growing on them. They are directly above the carpark at Queen's Road. The terrace breaks in slope are pronounced. It is presumed that these sloping terraces represent the earliest surviving evidence for landscaping of the area and date to the 17th century. The second area is to the south and consists of a walled garden divided into four linear terraces. It appears that these replaced the earlier curving terraces in the later 17th century. The third area is to the north and constitutes the modern park containing a Bowling Green, tarmacadam paths, flowerbeds, fountains, sculptures and other monuments. It seems to reflect 19th and 20th century landscaping.

The archaeological assessment carried out at

Lisburn Castle Gardens in 2003 established that the site contained

at least seven phases of activity:

![]()

Phase 1. Pre-Castle evidence.

No evidence of activity — in terms of structures, features or artifacts was uncovered dating to before the 17th century. From an archaeological perspective this is puzzling. The site, on a drumlin overlooking a natural river crossing and with all the facilities that a river provides (defence, transport, food, tribal boundary markers, etc), would have been most attractive to prehistoric, Early Christian or Medieval settlers. Perhaps the extensive landscaping that was undertaken when the Castle and gardens were created in the 17th century removed most of this evidence. It is very possible, however, that outside the limited areas investigated in the 2003 assessment, evidence of earlier occupation may survive elsewhere on site.

Phase 2. The creation of the Castle and Gardens

|

| Lisburn Castle Gardens. Overlay of 17th century Ground Plotte of Lisnegarvey map on 1968 OS map. |

The primary phase of landscaping appears to have taken place in the early 17th century, when the Castle and original curving garden terraces were created. The grass-covered terraces that survive primarily at the eastern side of the modern gardens were found, during excavation, to have originally extended around to the south and west, where they were replaced by a walled garden with widened, linear, terraces. There may also have been a fishpond at the extreme south of the garden complex, possibly uncovered during the excavations on what is now known as Terrace 4.

This first phase of garden use would appear to date to Sir Fulke Conway's erection of the Castle and gardens, probably in the 1620s. In 1631 the Conway family employed George Rawdon as their agent in Ireland.

The Castle

Visible remains of the 17th century Lisburn Castle no longer exist above ground. However, based on the plan of the building portrayed on the 17th century Ground Plotte of Lisnegarvey map, it is possible that it may have resembled the fortified manor house at Richhill, County Armagh built in the 1660s. The map seems to indicate that Lisburn Castle, like Richhill, was roughly E-shaped, with three projecting wings on its western front and buttresses to the north and south.

Phase 3. The evidence of possible battlefield archaeology

In Trench 5, approximately half way along the outer face of the east wall of the walled garden, fragments of a human mandible and teeth were recovered from a burial pit cut into subsoil. The human remains may relate to the 1641 Rebellion battle at Lisburn. The find raises speculation that Lisburn Castle Gardens also contains battlefield archaeology in the area outside the limits of the walled garden. This may further reinforce the archaeological potential of the whole site.

Phase 4. The later 17th century improvements

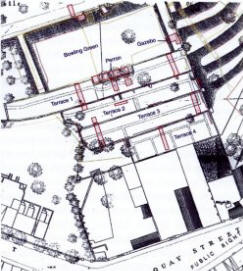

|

| Fig. 2. Map showing the location of the trenches excavated in 2003, overlaid on 1870 OS map of Lisburn. |

A second phase of garden improvements began in the later 17th century. It perhaps gathered momentum once the years of war in Ireland, which began with the 1641 Rebellion and ended with the campaigns of Cromwell and Ireton in 1653, were over and relative peace had returned to the country. During the wars, Lisburn was attacked twice. The first occasion, November 1641, saw a major battle in the town when both it and Lisburn Castle were damaged. The second occasion was in November 1649 and we are unsure what, if any, damage was done to the Castle and gardens.

George Rawdon married into the Conway family and was resident at the Castle in 1654. Letters back to the Conway's in England, starting in 1656, describe the improvements he was carrying out at the gardens. Perhaps the damage done to the Castle and gardens in the 1640s gave him a certain carte blanche to set out his vision for the new garden, in tandem with repairing the damaged property. These improvements included creating the walled garden, widening the terraces, infilling the fishpond, laying out paths, and constructing the perron and the gazebo.

Of these later 17th century works, the most visually apparent to the modern visitor is the walled garden encompassing the linear terraces, constructed to the south of the Castle. Most of these walls are still upstanding, though in various states of disrepair.

Within the boundaries of the walled garden were created four linear terraces separated by redbrick walls. During the 2003 excavation the Terraces were given numbers, 1 being the highest terrace, number 4 being the lowest. Excavation on Terraces 1-3 showed that the early 17th century, curving terraces had originally extended to the west of the garden but were later infilled with soil and revetted with redbrick walls to widen the width available for use. This improvement took place in the later 17th century. The fishpond, on what is known now as Terrace 4, was also infilled and a boundary wall constructed of redbrick was built across it.

The excavation provided the opportunity to examine the 17th century construction technique of the redbrick terrace walls. Where the walls have been fully uncovered, the evidence is identical. It appears that all soil was removed to subsoil level and stone footings inserted. Then a brick plinth was built on top of this and finally the wall constructed. When this was done, the subsoil was redeposited against the stone footings leaving only the brick base and wall proper visible at ground level.

What was not visible to the visitor when excavation commenced were the more ephemeral garden improvements carried out in the later 17th century. As revealed by the 2003 assessment these included on:

- Terrace 1: Gravel paths at either end of the terrace, oriented east-west; flower beds to north and south of terraces either side of the paths; field drains and flanking paths; different styles of brick build in the wall dividing Terrace 1 from Terrace 2.

- Terrace 2: A red brick-edged path, oriented east-west, and flower bed immediately north of it against terrace wall; a hedge row oriented north-south in the middle of the terrace; and the revelation that the red brick wall dividing Terrace 1 and Terrace 2 was of shoddy construction leading to it later bowing.

- Terrace 3: A gravel path, oriented east-west, and deep wall footings for the wall dividing Terrace 2 from Terrace 3, at the east end of the terrace; the collapsed terrace wall at western end of the terrace. Two gravel paths with flanking field drain; flower beds and pits, containing a 17th century tile, at the western end.

- Terrace 4: The fishpond infilled and built across with a red brick wall, flower beds and drills. Due to health and safety concerns the trench was not bottomed.

Phase 5. The perron and gazebo

|

| The 17th century perron on Terrace I, during excavation. |

The Perron: At some stage in the later 17th century a structure was erected along the middle of Terrace 1. The building consisted of a single story series of vaulted chambers fronted with red brick. (Fig.3) The central vaulted chamber, the main focus at this level, still contains the remains of a door and flanking windows.

On the roof of the structure was found evidence (imprinted on the mortar covering the roof) that there had originally been steps up via a half-platform from either side leading to a platform directly over the main vault. Only a few stones remain in situ at either end of the steps. The building remains substantially intact and currently appears to be structurally sound. Further excavation is required to determine the full extent of the structure at either end.

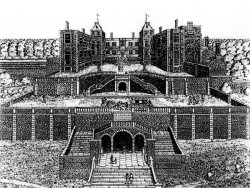

The building has been identified as a mostly intact perron, a high status viewing platform, and adds further evidence to the picture of Lisburn Castle Gardens as an important 17th century formal garden (Fig.4). The perron at Lisburn Castle Gardens is a rare survival in terms of the Irish garden archaeological record. It is not portrayed on the 17th century Ground Plotte map.

The Gazebo: Excavation of Trench 6, located at the south-eastern corner of the Bowling Green, uncovered the masonry remains of the basement of a gazebo or pavilion. The building dates to the 17th century.

The walls were found to be at least 2m deep, were rendered and contained shelf holes. The building was only partially uncovered and the walls were not bottomed. However, during the investigation an oven was located close to the inside face of the northern and eastern walls. This is a rare discovery as very few 17th century ovens have been identified on sites in Ireland.

It appears that the gazebo or pavilion survives in a fairly intact state at basement level and there is every possibility that the full extent can be uncovered. This work would help us determine the types of activities that were being undertaken within it and also reveal other architectural details such as flooring and internal layout. However, due to later disturbance and soil movement, the walls are currently in a dangerous state and stabilisation of the masonry will have to take place before further excavation can be carried out.

|

| Fig. 4. Thomas Cecil's house at Wimbledon, drawn in 1678, and broadly contemporary with Lisburn Castle Gardens. The illustration depicts several styles of perrons. |

Immediately north of the gazebo walls were uncovered the remains of a brick-edged path or cloister, leading to the building and running along the eastern side of the Bowling Green.

The excavation of the 17th century gazebo is the first of its kind in Ireland. Like the perron, the gazebo is not illustrated on any of the early maps but further reinforces the picture of Lisburn Castle gardens as a very important 17th century formal garden.

The survival of the perron and gazebo are of major importance. That these buildings were previously unknown prior to the 2003 archaeological assessment and, in the case of the gazebo, not even visible above ground, leads one to consider that other important garden features may remain to be uncovered at Lisburn Castle Gardens.

High quality artefacts dating to the 17th century

were found across the various areas excavated in the 2003 assessment.

These included English, German and Dutch pottery; decorated delft tiles;

clay pipes; goblet, window and flower pot glass; brooches, pins and

other metal work; cut sandstone and glazed roof tiles (possibly from the

Castle)

![]()

Phase 6. The 1707 fire and its impact on Lisburn castle and gardens.

The calamitous fire that took place in Lisburn in 1707 appears to have had a disastrous effect on the Castle and gardens. The Castle was levelled and never rebuilt, and the importance of the gardens went into subsequent decline and neglect. How much damage the fire caused to the structures that stood within the garden is not fully known, but it may have been considerable. Dr. Molyneux, who visited Lisburn the following year, wrote: `Vast Trees that stood round the Church Yard Burnt to Trunks. Lord Conway... his House, tho' at a distant from all the rest in the Town, burnt to Ashes, and all his Gardens in the same condition, with the Trees in the Church Yard...

The evidence from the top of the perron is clear. Virtually all the stone from the steps leading to the platform was removed, as was any high quality stonework that had originally been on top. If there had been a wooden balustrade ornamenting the steps and platform, then this would certainly have burnt. There is some evidence of burning on bricks on the perron façade, perhaps resulting from this episode.

At a later stage deep deposits of soil were dumped on top of the perron roof These deposits, investigated in Trenches 1D and 1E, contained masonry fragments, soils with a high charcoal content along with 17th and early 18th century ceramics. They have been interpreted as material from the demolished Castle that was dumped on top of the perron in the 18th century both as a means of removing it from the main area of the park and also to re-establish the top of the perron as a (basic) viewing platform.

It must also be noted that in the early decades of the 18th century there was a change in fashion from the formal to the informal garden, so the elements that Rawdon had introduced earlier may have been regarded as out of date.

This would have also contributed to the decision not to reinstate what had been there previously.

Phase 7. Activity at the gardens from the mid-18th century until modern times.

Between the mid-18th century and the present clay, Lisburn Castle Gardens was moulded into the form that would be familiar to visitors today. In the 19th century there were certainly attempts to manage the garden and terraces and a caretaker was appointed. These efforts were reflected in the pathway uncovered in Trenches 1C and 1G and the flower beds revealed in Trench 4, Terrace 4. It may also be the period when the stone wall was built over the brick remains of the perron, to afford a safe view down the terraces to the river.

However, although the main area of the park has been constantly looked after, it is clear that since the 20th century the terraces within the walled garden have been neglected.

As encountered in 2003, these were completely overgrown to the point that the perron was unrecognisable as having been such an important building until revealed by excavation. The terraces had clearly also been used as a clumping ground for all sorts of rubbish for a considerable period. It is ironic that this neglect has largely protected the remains of the 17th century formal garden from improvements in modern times and from techniques that have the potential to do irreversible damage.

The 2003 assessment excavation proved that the Bowling Green and terraces of Lisburn Castle Gardens are a time capsule, containing the substantial remains of a very important 17th century formal garden. A further season of excavation, conservation and restoration is planned for 2006. It can be confidently expected that more exciting discoveries will be made.

Note: Figs. 1-3 are the copyright of ADS Ltd.

Select Bibliography

| Bayly, H. |

| A Topographical and Historical Account of Lisburn... (Belfast, 1834). |

| Best, E.J. |

| The Huguenots of Lisburn: The Story of the Lost Colony (Lisburn, 1997). |

| Burns, J.F. |

| 'The Life and Work of Sir Richard Wallace Bart, MP', Lisburn Historical Society Journal, vol.3 (1981), pp. 8-22. |

| Brett, C.E.B and Lady Dunleath |

| List of Historic Buildings... in the Borough of Lisburn (Belfast, 1969). |

| Clarkson, 1..A. and Collins, B. |

| `Proto-industrialisation in an Irish Town: Lisburn 1820-21' Proceedings of VIII Economic History Conference, (Budapest, 1982). |

| Day, A. and McWilliams, P. |

| Ordnance Survey Memoirs of Ireland, Parishes of Lisburn and South Antrim II 1832-38, vol. 8 (Belfast, 1991). |

| Dixon, Hugh. |

| Aspects of the legacy of Sir Richard Wallace in the fabric of Lisburn', Lisburn Historical Society Journal, vol. 4 (1982), pp. 7-14. |

| Gillespie, R. |

| `George Rawdon's Lisburn', Lisburn Historical Society Journal, vol. 8, (1991), pp. 32-36. |

| Gillespie, R. |

| Colonial Ulster, The Settlement of East Ulster 1600-1641. (Cork, 1985). |

| Greene, W. J. |

| A Concise History of Lisburn and Neighbourhood. (Belfast. 1906). |

| Kerr, W. |

| `The last will and testament of Edward, 1st Viscount Conway and Killulthagh (1564-1631)', Lisburn Historical Society Journal, vol. 6 ( 1986-1987), pp. 14-19. |

| Lambe, K. & Bowe, P. |

| A History of Irish Gardening (Dublin, 1995). |

| Lalor, P. |

| The Huguenots in Ulster: an extract from Blaris Parish Register', Ulster Genealogical and Historical Guild Newsletter, i, 10, (1984), pp. 3-4. |

| Mackey, B. |

| Lisburn, The Town and Its People 1873-1973 (Belfast, 2000). |

| Mackey, B, |

| `The Market House and Assembly Rooms, Lisburn', Lisburn Historical Society Journal, vol. 6, (1986-87), pp. 44-57. |

| Mahaffey, R.P.(ed) |

| Calendar of State Papers of Ireland. (London, 1907-08). |

| McComb. W. |

| McComb's Guide To Belfast, The Giant's Causeway and Adjoining Districts of The Counties of Antrim and Down. (Belfast, 1861 reprinted by Wakefield, 1970). |

| 0' Laverty, J. |

| An Historical Account of the Diocese of Down and Connor. Vol. II (Dublin, 1880). |

| Warner, R. |

| `The Early Christian Ringfort of Lissue', Lisburn Historical Society Journal, vol. 6, (1986-87), pp. 28-36. |

| Warner, R. |

| The Lisburn Area in the Early Christian Period. Part 1: Setting the Scene', Lisburn Historical Society Journal, vol.7, (1989) pp. 24-30. |

| Warner, R. |

| "fhe Lisburn Area in the Early Christian Period. Part 2: some People and Places', Lisburn Historical Society Journal, vol. 8,(1991), pp. 37-43. |

| Young, R.M. |

| Historical Notices of Old Belfast and its Vicinity. (Belfast, 1896). |

| Young, R.M. |

| The Town Book of the Corporation of Belfast (Belfast, 1892). |