- Front Page

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Lisburn Seventeenth Century Tokens

- Mr. Stewart's Ballroom Near Lisburn:

- The Last Will And Testament Of Edward, 1St Viscount Conway And Killultagh (1564-1631)

- Chrome Hill, Lambeg

- The Early Christian Ringfort Of Lissue

- The Lisburn By-Election Of 21 February 1863

- The Market House And Assembly Rooms, Lisburn

- Bygone Days

- Historical Journals

Chrome Hill, Lambeg

ROBERT McKINSTRY

|

| The entrance front with 1760's doorway, carved stone surround and pediment. The original doorway was where the garden seat is placed. (photograph Ivan Strahan) |

During the eighteen years in which I have lived at Chrome Hill, I have tried to piece together the history of the house and its occupants. My particular interest has been to identify the changes made to the original 17th century building, over the three centuries of its existence. The result of my research will it is hoped, prove as interesting to the reader as it has been to me.

The original small farm dwelling, out of which the present house has grown, was probably built sometime during the second half of the 17th century by the Wolfenden family, who are generally thought to have come from the Low Countries1 and whose name is closely associated with the early linen industry in this area of the Lagan Valley.2 About the same time as they built their home, they established a paper making works nearby. This business was situated where the old Lambeg Weaving Company factory stands, between the Ballyskeagh Road and the Lagan. They also had a blanket making works on the Co. Antrim side of the river, beside the River Road.3 Chrome Hill was, therefore, both a farm house and a factory owner's home, and has continued to be so until the beginning of this century.

The earliest gravestone in the Wolfenden enclosure in Lambeg churchyard records the death of Jean Wolfenden `wife of Abraham Wolfenden deceased September ye 15th 1693 aged 43 years'.4 This Abraham may well be the Abraham Wolfenden referred to in the 1719 volume of the Hertford Estate's Rental and Account Books as having rented the mills at Ballyskeagh (their size being 25 acres 2 roods 31 perches) at a rent of £7 18s.5 If he was not the builder of Chrome Hill, he is its earliest known occupant. In 1690, he is said to have supplied the timber needed to repair one of King William's wagons, when it broke down at the ford over the Lagan, where the Wolfenden Bridge now stands. The King is said to have waited in Abraham's house, while the wagon was being mended.6

The `M. Richard Wolfenden of Lambeg, linen draper', referred to on one of the gravestones, was probably Abraham's son. He married Margaret Waring and died in 1743, at the age of seventy. His son, the second Richard (1723-75), married Jane Usher of Aghalee. Their son, the third Richard (17571816), married Mary Gayner, the daughter of Edward Gayner of Derriaghy, a friend of John Wesley. Wesley's Journal of 10 June 1787 records a visit to Chrome Hill. While he was there, he is said to have twisted two beech saplings together (to symbolize the continual union of Methodism and the Church of Ireland). and formed what still survives as two large intertwining beech trees, known as Wesley's Tree'.7 Richard's sister, Anne Jane, married another neighbour, John Charley of Finaghy House, who has served his time under her faThe last Wolfenden to be buried in Lambeg churchyard was John (1788-1829). Though a Thomas Wolfenden is recorded as being a Churchwarden in Lambeg Parish Church as late as 1886, the family had by this time moved to Dublin and become muslin factors at the Linen Ha11.9 In 1830, the Lambeg works, by then also producing cotton goods, calico and muslin, were sold to Richard Niven of Manchester.'10

It was Niven who rechristened the house Chrome Hill - it had earlier been known variously as Harmony Hill and Lambeg House - to commemorate his discovery of the use of bichromates for textile printing.11 He died in 1866,12 but his widow lived on at Chrome Hill until her death in 1899. 13 The previous year, the house had been purchased by John Milligen,14 a Belfast coal merchant and property speculator. He, however, only lived in it for a few years, before moving to Glenmore in 1901. He then rented the house to a Major Adam Jenkins and subsequently to Benjamin Hobson, whose family owned the linen works at Ravernet. In 1921. Milligen sold the house to F. G. Barrett and shortly afterwards, disposed of all his property in Lambeg, including Glenmore. In 1924, Barrett sold the building to Mrs. Downer, who remained in possession of the house for the next forty-three years. In 1967, after her death, Chrome Hill came on the market and my wife Cherith and I bought it.

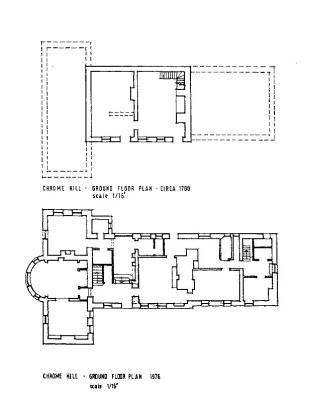

Abraham Wolfenden's original 17th century vernacular house 17th century vernacular house 15 can be unravelled from the later additions, by looking at the existing ground plan and taking particular note of the large, very deep chimney breast in the room which has always been the kitchen, immediately to the right as one enters through the front door. The unusually large scale of this chimney breast indicates that it must be the original hearth. with the front end forming part of the lobby to the first entrance door, the lines of which are still recognisable in an existing wall recess in this part of the front wall of the house. At the far end of this chimney breast, there was originally a small staircase which connected to the room or loft above. A few crumbling steps of this staircase can still be seen from inside the roof space, by means of shining a light vertically into and down through the first floor timber-framed wall, beside the sitting room fireplace. To my mind, such features as I have described, make it clear that Chrome Hill developed from a two unit, two storeyed or lofted house of hearth/lobby formation, with the stairs at the rear of the chimney stack between it and the back wall. This practice is commonly seen in English hearth/lobby houses of the 17th century, but is rarely found in Northern Ireland.16

Sometime around the 1760s (judging by the style of architectural detail), the original house was heightened, remodelled and extended, by adding a three storey wing on to the west side, three rooms long. The difference in floor levels between the old and new blocks, and the way they are set at right angles to each other, suggests that this wing may have already existed as a cloth store, positioned close to the house for security, giving the building a T-shaped form.

At this time, the front door was moved westwards by three

bays, to open into a proper little entrance hall, made out of the front part of

the second room in the original house. From here, a fine staircase was built to

a spacious landing (a duplicate of the entrance hall), which leads into a large

sitting room made out of the original loft above the hearth room.

![]()

These changes of the 1760s reflect the relatively more sophisticated, formal and even spacious life style of the 18th century factory owner. This is underlined by the architectural embellishments introduced as part of the improvements and sometimes applied with little regard for symmetry and regularity. Nevertheless, I am constantly aware that it is actually the effect of this robust classical detailing, laid over the very basic low set 17th century vernacular house, which gives Chrome Hill its unique character.

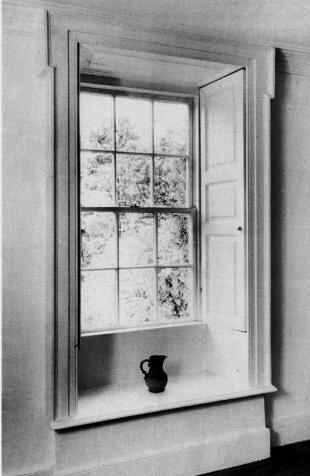

Much of this mid 18th century detail still survives intact. There is the carved sandstone pedimented entrance doorway with cushioned freize, and the lugged architraves which are found around nearly all the six fielded panel doors in the house and repeated in the window architraves. Behind these, all the panelled shutters are still in working order. A particularly attractive feature of these windows is the little window seat set well down below the actual window sill and carried out beyond the window reveals, to form a base for the architraves. There is a small fully panelled room which served as a library. There is, in addition to this panelling, good joinery work in the staircase - sturdy turned balusters, three to a step, and double newel posts. Above the main staircase and hanging over it, rises the little winding attic stairs, which disappear into the ceiling in a delightfully unexpected way. Equally charming is the little semi-dome which forms a sloping archway over the four steps from the first floor landing, to two of the bedrooms in the west block. This archway theme is repeated below, at each end of the entrance hall. The 18th century cornices only survive in the hall above the staircase, on the landing and in the room at the back of the hall (now lower hall). Here, on the ceiling, is the only example of decorative plasterwork: two rectangular panels with reeded frames, containing rococo scrolls and central circular panel with the Wolfenden arms, consisting of a chevron between three wolves' heads.

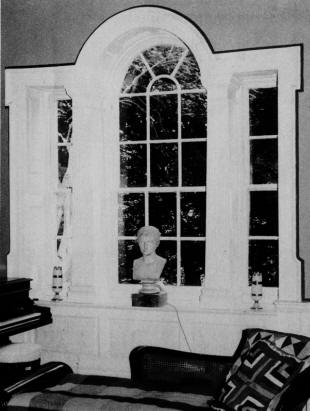

Probably the finest architectural flourish is to be seen in the first floor sitting room, with its large Venetian window in the back wall, facing north, and its panelled dado containing two little `secret' jib doors. That on the right side of the gray and white marbled mantel was once a cupboard, while that to the left opened on to the hearth staircase. However, the 17th century origins of the room are still obvious in the two corner windows facing south. These have hardly any vertical architraves at their comer sides, because the original low loft window openings which form part of the taller 18th century openings, were built tight against the long side walls. Likewise, the corner position of the front door opening in the entrance hall means that there is no architrave at all on the left hand side.

An ambitious rebuilding such as I have described is usually only undertaken when a new generation or a new owner takes over. In this case, it was probably the second Richard Wolfenden, who, at the age of twenty, succeeded his father in 1743. The work may well not have been carried out until after he had married Jane Usher.

Probably soon after Richard Niven bought Chrome Hill and the factory on the other side of the road, he set his crest (like a seat on the house), into the stone pediment above the front door. He must also have built the elegant two storey late Regency style elliptical curved bow as an extension to the middle room on the west side of the house. By doing this, the middle room became a comparatively spacious dining room, with flat fluted pilasters marking, on the old walls, the position from where the new bow front springs. The wall opposite was remodelled as a kind of screen of three segmental arches, the wider central archway framing a sideboard recess, and the doors each side (one to a cupboard, the other to a little entrance lobby) surmounted by a smaller blind arch with architraves similar to the pilasters. Outside, the tall painted timber mullions and transomes in the bow contrast happily enough with the earlier double-sash twelve-light windows in the rest of the house.

In Richard Niven's time, there were two ways into the house. Firstly, there was the old drive" (reputed to be part of the original road south) which started at the high canal bridge, ran west across a large field flanking the stable yard on its north side, then along in front of the house, finally coming out onto the road again, just at the river bridge (now known as Wolfenden Bridge).18 Secondly, there was the steep driveway up to the stable yard and the back of the house, from the road immediately opposite the factory entrance. Sometime before the 1860s, Niven made a new main entrance just west of this secondary entrance, with the driveway describing a wide semicircular sweep up to the front door. This gave the visitor the best view of the west front of the house, and its new picturesque bow. By this alteration, that part of the old driveway which ran straight from the house down to the river, was made redundant and eventually disappeared. However, the other part, that from the canal bridge, survived into this century and though the little lodge house has gone, part of the gates still stand, in a ruinous condition. Both Niven's new entrance gates and the entrance eastwards (that opposite the factory), with its original 18th century gates and piers, are in use today.

The Edwardian alterations were probably made by John

Milligen, when he lived in the house for a short time, in 1900. The entrance

hall was enlarged by taking in the back room off the hall and lowering its floor

level to the level of the lower ground floor room behind the stairs. This

created additional height in at least part of the hall, and the two rather

disparate spaces were united by a wide archway, with four stone steps spanning

the full width of the opening. A large leaded stained glass window, in an Art

Novena design of pale blue-green, was inserted in the back wall, casting light

on the black, red and white encaustic tiled floor. There is a smaller version of

this hall window in the extension built out from the staircase half landing,

which one enters by what was the original staircase window, and which was built

essentially to house the outside cold water storage tank. This tank serves the

pine sheeted bathroom and cloakroom, made at the same time within the walls of

the house. From this period, also, must belong the curious little Smoke Room (so

labelled on the old room bell indicator board) at the top of the house, with a

sort of panelled vaulting created out of the slopes in the interlocking roofs.

This would have been the date at which the house was pebbledashed. The stone

quoins which are visible on an old photograph, were cut back and cemented over

at the same time.

![]()

When we came to live at Chrome Hill in 1968, we had general repairs carried out, new central heating installed, the building rewired and fully painted. The exterior pebbledash was painted white. We made the old kitchen into a children's playroom and turned the little panelled library beside the dining room into a new kitchen, making sure that the panelling was left as undisturbed as possible, and using the built-in bookcases as storage cupboards. This new kitchen and the dining room were connected by a new doorway with shutters, so that the two rooms now function as one.

I removed the chimney stack and the two small windows on either side of it, from the top of the south gable wall of the west block, and substituted these for a large semi-circular window. I also remodelled the dormer window and door leading on to the balcony of the west bow, so that it is now more Georgian in appearance.

Perhaps the most significant addition we have made has been the large carport attached to the north side of the house, with its gable end at right angles to the building. The idea was to try and make this little structure look like an 18th century farm building on one side and a garden pavillion on the other, one side of the carport being linked to a paved terrace I had already made on this particular side of the house. Therefore, the open long side of the carport has two simple creosoted timber columns dividing its length into three, while the other long side has three arched openings with sheeted shutters, which can be left open or shut, depending on the weather.

What has it been like for Cherith and me and our three boys to live in this old multilayered house, with its feeling of still being in the country (despite being quite close to town)? Above all, there has been the joy of space and light and plenty of room. Yet the scale is intimate and there is a mystery about the way rooms lead into each other, which children love and grown-ups can find disconcerting. The place looks its best in spring or autumn sunlight, when the trees are not heavy with leaves, and a slanting light pours through the old windows, across the panelled shutters and onto the boarded floors. The past is very near then. This is how I like to remember it when I'm away.

REFERENCES

| 1. | Rev. H, C. Marshall, The Parish of Lambeg, 1933- p. 39. In the notes on the Wolfendens of Lambeg, kindly given to me by Robin Charley in 1981, it is claimed that the family came here from Yorkshire. Francis Joseph Biggar, in the Ulster Journal of Archaeology, vol. VII, January 1901, states that the Wolfendens were Huguenots but I cannot find any evidence of this |

| 2. | E. R. R. Green, The Industrial Archaeology of County Down, 1963, p. 27. |

| 3. | `King William's Progress to the Boyne -No. 2', Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 1853, vol. 1, pp. 135-6. |

| 4. | Details of the inscriptions on the Wolfenden graves in Lambeg me given in Marshall, op. cit., pp. 38-9. |

| 5. | P.R.O.N.I., D427/1, p. 102. |

| 6. | Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 1853, toe. cit., pp. 135-6. |

| 7. | Frederick C. Gill. In the Steps of John Wesley, 1962. |

| 8. | Robin Charley's notes, as above, no. 1. |

| 9. | Green, op. cit., p. 27. |

| 10. | Ibid. |

| 11. | Lewis's, Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, 1837, vol. 11, p. 243. The Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 1853, loc. cit., calls the building Lambeg House. Robin Charley, in his notes, states that the original name was Harmony Hill, as does Burke's Irish Family Records, 1974, p. 222. |

| 12. | Marshall, op. cit., p. 32. |

| 13. | Marshall, op. cit., p. 33. |

| 14. | Marshall, op. cit., p. 113, lists the occupants of Chrome Hill. |

| 15. | Alan Gailey, Rural Houses of the North of Ireland, 1984, p. 188. |

| 16. | Gurley, op. cit., p. 171. |

| 17. | Thomas Pattison's map of the parish of Lambeg, drawn c.1830 (P.R.O.N.I.), shows the old drive like a roadway running in front of the house, down to the river. |

| 18. | The First Edition 0.5. map (Antrim, Sheet 64, 6" scale, 1833) shows the old road down to the Wolfenden Bridge, while the Second Edition 0.8. Map (Antrim, Sheet 64, 1904) shows Niven's new driveway. |

Robert McKinstry is a well-known local architect, with a particular interest in the restoration of old buildings. His most important commission has been the refurbishment of Belfast's Grand Opera House. He was also responsible for the remodelling of the assembly room in Lisburn Museum.