LISBURN LINKS TO ULSTER'S

WORST EVER

FERRY DISASTER RECALLED

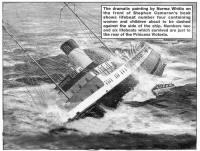

NEIL GREENLEES LOOKS AT A NEW BOOK ON THE PRINCESS VICTORIA SINKING

A NEW book about the tragic loss of the car ferry Princess Victoria while travelling from Stranraer to Larne almost 50 years ago recalls three local people who were on board when she set out on what was to be her final voyage.

Thomas Ronald Curry (34), who lived at Donard Drive in Lisburn, had been a frequent traveller on the vessel during his two years as a chargehand electrician at Short Brothers and Harland's factory on Wig Bay, close to the Scottish ferry port.

David

Peter McGarry who was in his mid-20's came from Milfort Avenue

in Dunmurry.

David

Peter McGarry who was in his mid-20's came from Milfort Avenue

in Dunmurry.

He too was an electrician at the factory and was making his third crossing on the ferry.

Both survived the tragedy. However, their colleague at the Wig Bay premises - William McClenaghan from Carryduff - did not.

The keen sportsman, who played for Saintfield Cricket Club, had been married for just 10 months and his wife was expecting their first child. The book 'Death in the North Channel' by Stephen Cameron describes in detail the tragedy which younger generations may not be aware of but which claimed 135 lives.

When it occurred it had the same devastating effect on Northern Ireland as the Kegworth air crash almost 40 years later.

Particularly chilling was the fact not one woman or child survived the ship's sinking - all 44 survivors were men.

The disaster occurred on Saturday January 31, 1953 during weather conditions which are still referred to as 'the great storm'.

Mountainous waves were created in the North Channel as winds blew at anything up to Force 12.

Mr. Curry, Mr. McGarry and Mr. McClenaghan all boarded the Princess Victoria at Stranraer around 7am.

They immediately ate breakfast in the third class dining room (there were only two classes of travel on the vessel first and third. Third was in fact the equivalent of today's tourist class and not the steerage of earlier in the 20th century).

The three then settled down with their fellow travellers, many of whom arrived on the overnight sleeper from London, for what promised to be an uncomfortable crossing.

About this time wind speeds at Helens Bay in the comparative shelter of Belfast Lough were being recorded at between force seven and nine with gusts up to 70 knots.

BBC Radio was warning of severe northwesterly gales in the

Irish Sea and another vessel, the 'Lairdsmoor', dropped anchor

in the Lough after encountering hurricane force winds.

![]()

Yet at 7.45am the Princess Victoria - with her open stern protected only by five foot high doors - set sail for Larne.

Her progress up Loch Ryan was slowed by the heavy weather and it took about an hour to reach the open sea where the storm had strengthened to produce waves well in excess of 45 feet.

Accounts from eyewitnesses who watched the vessel from the land which surrounds the mouth of the Loch have revealed it is entirely possible Captain Ferguson attempted to turn back into its sheltered waters and wait for the worst of the storm to pass after witnessing the sea state.

However, this move directly exposed the rear doors to the waves created by the north westerly gale, the force of the water carrying away their bolts and flooding the car deck to a depth of one and a half feet.

The massive wave which did the damage knocked some passengers in the lounges from their seats.

Attempts to shore up the damaged car doors proved useless as did efforts to engage the bow rudder and thereby reverse back into Loch Ryan.

Captain Ferguson then made the difficult decision to try and cross to Larne.

At around 10am the three local men and their fellow passengers were warned to expect heavy rolling but assured they were quite safe by an announcement over the public address system.

However, at 11.00am as the listing ship over which the crew now had little control drifted southwest-wards towards Belfast Lough they were told to put on lifejackets.

Mr. Curry assisted the crew in handing these out as the Princess Victoria continued to list severely. By 1.00pm it was impossible to walk around the vessel without the aid of lifelines which had been run throughout the passenger accommodation.

The Donard Drive man and his two colleagues were among those who helped the women, children and less able passengers make the ascent to open deck after they were told to get as high as possible in the ship.

By this stage the tonnes of water which continued to enter the ferry had caused it to list to around 60 degrees and at 1.30pm the passengers were told to assemble on the weather deck and standby to abandon ship.

When speaking of the disaster Mr. McGarry described how he was surrounded by men, women and children clinging to the siderails which were almost above their heads.

He was close to the bridge and heard Captain Ferguson shout that if the Princess Victoria had to be abandoned every_ one was to try to get into either a lifeboat or a raft. The entrance to Belfast Lough and the Copeland Islands were clearly visible but the ship was turning over and people were beginning to be washed into the sea.

A number of women and children were helped into a lifeboat but this was dashed against the side of the vessel and the occupants thrown into the icy water - all perished.

Two more lifeboats were launched and those who still had

the strength attempted to board them. Within minutes the ship

rolled over on her side and more passengers were washed away

but others managed to climb on to the hull.

![]()

Among them was Thomas Curry who successfully got into lifeboat number six, the one in which most survivors were found.

David McGarry, meanwhile, jumped into the water and swam to another boat.

He clung to one of the lines hanging from it and after some minutes managed to get over the side and was hauled in.

William McClenaghan also jumped into the sea and swam with another man towards a liferaft.

The other man was able to get on to the raft but it was

carried away from Mr. McClenaghan by the heavy seas.

The Princess Victoria then 'turned turtle' and slowly slid

under the waves.

As she went down buoyant life rafts attached to the rear of her promenade deck broke free and these saved several lives.

As she settled on the sea bed a desperate struggle for survival began hundreds of feet above as people in the water attempted to get on to one of the three lifeboats or any of the rafts now floating at the scene of the disaster.

All this time a rescue operation was in full swing as the seriousness of the ferry's position became apparent.

Details of this operation which involved aircraft, lifeboats and other ships are outlined in the sad yet fascinating book which also explains how the situation was complicated by mistakes about the actual position of the ferry.

But sadly, all of this help arrived too late for the four children, 29 women and 102 men who died almost within sight of Donaghadee.

|

Survivors picked up by naval vessel DAVID McGarry was one of six men picked up by the naval vessel HMS Contest from the Princess Victoria's Lifeboat Number Two. Thomas Curry was rescued by the Donagadee Lifeboat from Lifeboat Number Six. The words `trauma' and `counselling' were not in ' common usage in 1953 and there was little compensation for those who had survived the terrible ordeal. Nor was there any compensation for the baby boy William McClenaghan's widow gave birth to after his death. He was named after his father. The inquiry into the disaster ran for 22 days in March 1953 at Crumlin Road Courthouse and the book details how it looked at a number of issues including the stern doors, the adequacy of the scuppers for removing water from the car deck and even the design of lifejackets which it emerged may have when they entered the water. The report prepared following the inquiry found the loss of the Princess Victoria was caused by its owners and managers in the following ways.

They failed to report this incident as required under the Merchant Shipping Act of 1894. An appeal was launched later in the year by the British Transport Commission and the ship's Registered Manager Captain J. Reed. The Captain's appeal was allowed but Northern Ireland Lord Chief Justice Lord McDermott dismissed that of the Commission. He stated they were negligent on two counts: by not taking appropriate steps to ensure water could be drained from the car deck and for failing to make the stern doors strong enough to withstand heavy seas. As always, lessons were learned front the disaster. Stern doors on similar ships were strengthened and the size of scuppers increased. However, this was of little consolation to those left behind to mourn their loved ones who perished in the icy waters so tantalisingly close to land. 'Death in the North Channel' is available in bookshops at a cost of £13.99. It looks set to become the definitive reference work on the subject of the Princess Victoria. Its author Stephen Cameron is already well known as the author of 'Titanic: Belfast's Own'. |