|

APPENDIX

Other Stories and Pictures of '98.

THE BATTLE OF BALLYNAHINCH

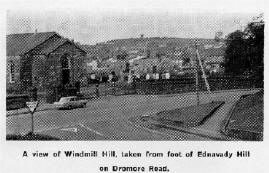

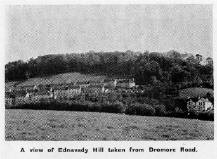

THE EVENTS leading up to the Battle of Ballynahinch - the Saintfield

skirmish, the insurgent encampment at Creevy Rocks, Monro's advance upon,

and occupation of, Ballynahinch, his first collision with the Military on

Tuesday evening, 12th June, when he withdrew from the town and Windmill Hill

and concentrated all his forces on Ednavady Hill -- are adequately dealt

with in the main story of this book. THE EVENTS leading up to the Battle of Ballynahinch - the Saintfield

skirmish, the insurgent encampment at Creevy Rocks, Monro's advance upon,

and occupation of, Ballynahinch, his first collision with the Military on

Tuesday evening, 12th June, when he withdrew from the town and Windmill Hill

and concentrated all his forces on Ednavady Hill -- are adequately dealt

with in the main story of this book.

As for the main battle, which commenced at 3 a.m. on the morning of

Wednesday, 13th June, we present readers with some additional details.

The insurgents numbered between 5,000 and 7,000 but more than a thousand

had deserted during the night. The military numbered between 2,000 and

3,000. In artillery Nugent had six six-pounders and two howitzers, while

Monro had only eight one-pounder swivel guns mounted on common cars.

Nugent's principal officers were Major General Barber in charge of

artillery, Colonel Leslie and Lt.-Col. Stewart, while Monro's chief officers

were James Townsend and Dr. Valentine Swail.

It would seem that it was part of Monro's plan to advance a strong force

on his right flank through the demesne to the east, to cross the river at

the Mill Bridge (on the road from Ballynahinch to Clough), then north across

the Mill Fields to attack Nugent's headquarters on Windmill Hill. Foreseeing

this, Nugent dispatched Lt.-Col. Stewart with the Argyll Fencibles, three

companies of Yeomanry, part of the 22nd Dragoons and Yeomanry cavalry, with

one six-pounder and a howitzer to enfilade the insurgent right flank.

Accordingly, Lt.-Col. Stewart made his way from Windmill Hill down the Mill

Fields, and up Crabtree Hill towards old Magheradroll churchyard, from which

position he could fire into the demesne lands.

THE BRIDGE STREET SECTOR

The battle began at 3 a.m. with artillery attacks on both fronts. Nugent

placed two of his six-pounders in Bridge Street (now Dromore Street) to

support the Monaghan Militia against the insurgent attack led here by Monro.

One participant on the insurgent side described the action thus - "We were

obliged to go up in the face of a party of the Monaghan Militia who did not

fail to salute us with a brisk fire. We ran up like bloodhounds and the Monaghans fled into the town where they kept up a kind of broken fire which

we returned, although only about twenty of us were armed with muskets. We

obliged them to take shelter in the houses twice". Street (now Dromore Street) to

support the Monaghan Militia against the insurgent attack led here by Monro.

One participant on the insurgent side described the action thus - "We were

obliged to go up in the face of a party of the Monaghan Militia who did not

fail to salute us with a brisk fire. We ran up like bloodhounds and the Monaghans fled into the town where they kept up a kind of broken fire which

we returned, although only about twenty of us were armed with muskets. We

obliged them to take shelter in the houses twice".

As may be gathered from the above, fighting in this sector was severe.

Captain Henry Evatt, adjutant of the Monaghans, was shot dead, Lieut. Hillis

wounded, and the army was forced back up Bridge Street.

Meanwhile, Monro sent a fresh detachment over the bridge, and turning due

east they crossed the field to reach Church Street near the parish church.

This force soon made contact with the main attacking party at the head of

Bridge Street and together they pushed the army back to the Market Square.

Despite musketry cross-fire, and grape and canister shot which took heavy

toll, and the fact that the ammunition for their musketry was expended, the

insurgents pressed forward with pike, bayonet and sword, driving the

military down Meeting-House Street (now Windmill Street) towards Windmill

Hill.

A cavalry charge against the insurgents failed, and the 61b. balls for

Nugent's cannon became exhausted (when leaving Belfast in a hurry a pile of

91b. arid 121b. balls had been put tip in mistake). It was at this juncture

that Nugent ordered a general retreat. But the insurgents mistook the bugle

call as the signal for a charge (or a summons for reinforcements) and they

hesitated and gave way. General Barber seeing this, ordered the troops to

the charge, and pursued the enemy through the town.

THE MILL BRIDGE FLANK

During this time heavy fighting took place on Monro's right flank, in the

region of Mill Bridge. What had been intended as an attack by Monro was

forced to become a defence in which all the advantage lay with the military,

they having the greater artillery support.

General Nugent in his dispatch to Lt.-General Lake describes this part of

the action thus -- "Lieut.-Col. Stewart now advanced within two hundred

yards of the main body of the Rebels, who made three different attempts with

their musketry, supported by a very great number of Pikemen, to dislodge

him, but were completely beat back by the steadiness and firmness of the

Argyll Fencibles and the Yeomanry, covered by the Howitzer and the gun

served with grape shot, which killed a great number of Rebels, many of whom

they carried off, notwithstanding our heavy fire . . . Lieut.-Col. Stewart

took possession of their strong post on the Hill where lie found their eight

guns with a great quantity of ammunition, their Colours, Cars, Provisions,

etc. - a very considerable number of the Rebels who were concealed in the

Plantation near Lord Moira's House were killed there . . . "

The defeat of the insurgents on Ednavady Hill was almost simultaneous

with their retreat in the town. Tire cavalry was ordered in chase, and the

defeat became a rout, many being cut down as they fled to seek refuge in the

countryside.

CASUALTIES

The losses on both sides can only be guessed at. One account of the

battle says: "In the conflict from 80 to 100 of the insurgents were killed

and many wounded. Of the army it could never be ascertained what number was

killed, as their dead and wounded were carried off in tumbrels. There were,

it is thought, about 40 killed, or perhaps more".

General Nugent claimed to have killed 300 in the actual fighting and 200

in the pursuit, and the killing and destruction continued for some days. The

army casualties admitted by Nugent were low to the point of absurdity - "one

captain and I believe 5 rank and file killed and one lieutenant and about 16

rank and file wounded . . . and several yeoman infantry killed and wounded".

During their occupation of the town the military burned and pillaged: 63

houses were burned; 69, including the houses of worship, were left standing.

"EYE-WITNESS ACCOUNT"

Professor James Thomson (father of Lord Kelvin), who lived at Spamount,

and was a boy of twelve at the time, wrote an interesting eye-witness

account of the battle in 1825. In it he states that on their arrival at

Ednavady Hill on Monday, 11th June, the insurgents dispatched parties in all

directions to collect provisions and bring in the United Irishmen. They were

more successful in the former (mainly by using threats), than in the latter

as the men of Ballynahinch and neighbourhood in general chose to retire to

Slieve Croob and adjoining mountains. Thomson accompanied women folk of his

own family with provisions to the insurgents. They were well received and

conducted through the camp, shown pikes, cannon and ammunition, which the

leaders pointed out to them. The men did not have uniforms, but were dressed

in "Sunday clothes". All wore something green, and some of the leaders had

green coats and yellow belts.

In arms, the majority had pikes. Some of the men had old swords, and

those of the higher class had guns.

Professor Thomson described the scene of battle as witnessed from a hilltop

near his home at Spamount. The approach of military from Belfast was

"announced by the smoke and fumes of farm-houses which they set on fire

indiscriminately. Inhabitants who had not yet deserted their dwellings began

forthwith to remove such articles as appeared valuable, or could be most

easily concealed . . A person in the neighbourhood concealed upward of a

hundred guineas in a magpie's nest in a high tree".

The battle on the 12th started at 6 p.m. and went on until dusk, and

consisted chiefly of cannon and musketry. A great many of the rebels

deserted, and the more determined were heard shouting to stop the runaways.

Between two and three in the morning the King's forces set fire to houses

in the town and the rebels with their small artillery tried to arrest the

work of devastation. The Royal army recommenced the cannonade with heavier

fire than before. A detachment with pieces of artillery flanked the

insurgent forces and their success contributed in a considerable degree to

the success of the military.

After mentioning the attack in Bridge Street and the centre of the town,

Professor Thomson continued: "During this part of the engagement which

continued for a considerable period we distinctly heard the cheers, the

yells and the shrieks of the combatants .

it is certain that the King's forces did not at that time succeed in their

intention (to dislodge the rebels from their position). The rebel army,

however, was suffering constant diminution by desertion, and their fire was

gradually slackening and had almost ceased, it is said, from want of

ammunition, about seven in the morning."

THE CRUEL FATE OF BETSY GRAY AND HER COMPANIONS

|

|

This miniature of Betsy Gray, which is in the possession of Mr. C. J.

Robb, Spa, was first published in the 1920's in a booklet "Out in '98". It

was reproduced from a painting by a man called Newell of Downpatrick, who

posed as a United Irishman prior to 1798, but who was, in fact, in the pay

of the Government. |

THE TRAGEDY OF BALLYCREEN

A SLIGHTLY different account from that by W. G. Lyttle of the murder of

Betsy Gray is given in "McComb's Guide", published in 1861 (about 30 years

before Lyttle's publication). It states "She went into action (at the Battle

of Ballynahinch) with a brother and lover, determined to share their fate,

mounted on a pony, and bearing a green flag. After the defeat the three

fled, and on their retreat they were overtaken by a detachment of the

Hillsborough Yeomanry Infantry, within a mile and a half of Ballynahinch.

"She was first come up with, the young men being at a little distance,

seeking a place for her to cross a small river, and could easily have

escaped. She refused to surrender; and when they saw her likely to fall into

the hands of the yeomen, they rushed to her assistance and endeavoured to

prevail on the captors to release her, offering themselves as prisoners in

her stead. Their entreaties were in vain. Her brother and her lover were

murdered on the spot. She still resisted; and it is said that a man called

"Jack Gill", one of the cavalry, cut her gloved hand off with his sword. She

was then shot through the head by Thomas Nelson, of the parish of Annahilt,

aided by James Little, of the same place. The three dead bodies were found

and buried by their friends. Little's wife was afterwards seen wearing the

girl's ear rings and green petticoat."

It is local tradition that Betsy and George Gray and Willie Boal were

killed at the corner of what is known as Horner's Road near the farm of

James Henry McMaster, and that the bodies were carried over rocky fields to

the hollow in which it was easier to open a grave.

The land on which the grave is situated belongs to Mr. John Dunlop, but

it remained in the Armstrong family (who found the bodies) until the present

century.

The Yeoman from Annahilt who murdered Betsy Gray became most unpopular.

Mr. Hugh McCann, Drumkeeragh, Dromara, informed us that his father, Mr.

Terence McCann, a local historian who was born about 1850, said the

parishioners of Annahilt Church wouldn't sit in the same pew as the Littles,

and that their children were stoned at school.

The women of the Little family were seen wearing parts of Betsy Gray's

clothing and ear rings, and a man who was employed by the Little family in

the early years of this century, stated in a letter that he saw the green

dress in a box in Little's house. (This letter is in the possession of Mr.

C. J. Robb, of Spa.)

WRECKING OF MONUMENT

Mr. James Mills, of Antrim Road, Ballynahinch, who was born in 1882, was

present when a number of local loyalists destroyed the

( monument on Betsy Gray's grave in 1898 - but it was in no disrespect of

Betsy's memory that they did so: neither was it the contrary.

"There was to have been a special ceremony at the grave on that Sunday to

mark the centenary of the '98 Rising," said Mr. Mills, "and local

Protestants were inflamed because it was being organised by Roman Catholics

and other Home Rulers. They didn't like these people claiming Betsy, and

they became so enraged that they decided to prevent the ceremony from taking

place, so they smashed the monument with sledge hammers."

Those involved in the wrecking included Mrs. Watt and her three sons;

William Simpson, James Samuel McMaster, James and Samuel Quinn, Samuel

McCaughey, and men called Duffield and Totten.

When the parties, mainly from Belfast, began to arrive in horse drawn

carriages for the centenary ceremony, several scuffles took place, and the

reins of the horses were cut by the locals, the horses scared off and the

carriages "couped." One Catholic named John McManus of Ballykine, who was

known in the district as "a decent man," was saved from his pursuers by Mr.

John Magowan, brotherin-law of Mr. Mills.

Down the years pieces of the granite stone were removed as souvenirs and

taken all over the world, and the railings from the grave were fashioned

into horse-shoes by James Martin, who then had the blacksmith's shop at

Magheraknock. He gave these to many of his friends, and one is in the

possession of Dr. A. R. Hamilton of Ballynahinch.

Mr. Edward Totten, of Lisburn Street, Ballynahinch, who is two years

younger than Mr. Mills, has confirmed the above facts.

WHERE MONRO WAS BETRAYED

THERE IS a tradition (which corresponds with Lyttle's story) that Monro

was captured at what is now Mr. Thomas McKeown's farm in Clintnagooland

(between Ballynahinch and Dromara, where he was betrayed by William Holmes

and his wife.

However, Mr. Robert Gray, of Church Street, Ballynahinch, says Holmes at

that time lived in a house in Burren, about half a mile on the Ballynahinch

side of McKeown's, and on the north side of the road. The house is now in

ruins.

"The reason for the misunderstanding," said Mr. Gray, "is that Robert

Holmes, a grandson of the couple who deceived Monro, was bequeathed the

house which is now McKeown's and he lived there until about 1910. The

property was next owned by Peels for a time before the McKeowns purchased

it. During the years when Lyttle and others were doing research into the '98

Rebellion, Robert Holmes resided in this house, and that is how the mistake

arose."

An old lane leads from the house down to the Dromore Road and it was

along it that Monro was taken on his journey which led to Dromore, and from

thence to Lisburn and the execution block.

The Holmes family became so unpopular in the district that they

eventually left Ballynahinch to live in Antrim.

William Holmes was buried in Dromara Parish Churchyard, and Mr. Gray

recalls attending the funeral of Robert Holmes in 1924, when he was interred

in the same grave. So far as Mr. Gray is aware, there are no relations now

in the Ballynahinch district.

Mr. Gray's father took a keen interest in the history of the '98 period

and passed most of his knowledge on to him. He is a relative of the late Mr.

Thomas Gray of Tullyniskey, Dromara, who claimed to be connected with the

Betsy Gray family.

THE McKEE FAMILY WHO WERE BURNED

AFTER THE PUBLICATION of an article in the "Mourne Observer", Newcastle,

Co. Down, by a correspondent signing himself as "The Student", which

suggested that the McKee family of Saintfield may not have been as `black'

as they were painted by W. G. Lyttle (see Chapter 30) the following letter

was received from an authoritative source: --

Although it is doubtless an excellent axiom not to speak ill of the dead,

I feel that "The Student" is perhaps too keen to whitewash the unfortunate

McKees. One cannot condone their murder - the only atrocity committed by the

insurgents in Co. Down - but in fairness to the rebels one must point out

that for two years prior to the rebellion a veritable reign of terror

existed in the Saintfield neighbourhood, and the McKees were largely to

blame. In March, 1797, the McKees tried to have eleven of their neighbours

hanged on a false charge of attacking their home. Although it is doubtless an excellent axiom not to speak ill of the dead,

I feel that "The Student" is perhaps too keen to whitewash the unfortunate

McKees. One cannot condone their murder - the only atrocity committed by the

insurgents in Co. Down - but in fairness to the rebels one must point out

that for two years prior to the rebellion a veritable reign of terror

existed in the Saintfield neighbourhood, and the McKees were largely to

blame. In March, 1797, the McKees tried to have eleven of their neighbours

hanged on a false charge of attacking their home.

A few details of the murder may be of interest. William Dodd, who owned

the ladder used in the attack, was a rebel whose wife was a sister of Samuel

Adams, who was attacked by Nelly McKee. Twelve were hanged for the murder -

William McCaw, William Shaw, James Breeze, hanged 23rd March, 1799; Hugh

McMullan, James Collins, Andrew Morrow, James Morrow, Robert Glover, David

McKelvey, James Hewitt, Thomas McKeever and Samuel HewAt, hanged 6th April,

1799.

Charles Young accused only James McNamara, William Shaw, Hugh McMullan

and John McKibben of the murder. James Gardner accused James Breeze, James

Collins, Rev. Adair, James Shaw, sen., James Shaw, jun., Thomas McKeever,

John Thompson, William McCall, James McCall, James Swan, William Keown,

William Gill, jun., Patrick Miskelly, David Hamilton, James Hammil, Samuel

Sibbet, Thomas Torney, Rev. Warden, Archibald McCann, Andrew Morrow, James

Morrow, Robert Glover, David McKelvey, Samuel Hewitt, Hans Shaw, Thomas

Coulter, Arner Phillips, James Sibbet, Samuel McCann, Adam Finlay, and -

Wallace, a deserter from the Breadalbane Fencibles.

The attack on the McKees was apparently made in two waves. An

eye-witness, Betty McCall, said she did not know any of the attackers,

except James Shaw, who was dressed in a green jacket. She heard it was a

fiddler named Orr, who lived between Saintfield and Killyleagh, who set the

house on fire. She saw John McKibben, a Saintfield surgeon, who was armed

with a pistol, march up with the first party.

Catherine Quinn, another eye-witness, later told that she stood at the

rock opposite her own house while the second party marched up to the attack.

She and three friends, Mary McMaster, Susanna

McMaster and Ellen Murray, watched the attack and burning of the house,

and waited till the attackers returned to Saintfield. The only attacker whom

she knew was Charles Young, who was armed with a pitchfork. She saw Flora

and Betty McCall come up from the Saintfield direction after the second

party had marched past, and go towards their own house in order to avoid the

shots.

It is remarkable that most of those accused of the murder were not

natives of the district. Keown and Glover hailed from Ballymoran; Torney,

the Morrows and Hewitts from Killinchy, the Sibbets from Balloo, the Breezes

from Toye, and McKelvey from Ballymacreely. Keown was the son of the

kilnsman at Ravara Mill, and James Swan was the son of the miller. The only

local man hanged for the murder was William McCaw, a weaver in

Carricknaveagh.

"The Student" replied, acknowledging the authority of above, but

respectfully submitting that since so few local United Irishmen took part in

the affair, those who murdered the family did not know the full facts. After

all, the McKees openly declared their loyalty and were not sly informers.

"The Student" also said that although this is the only (recorded) atrocity

committed by the insurgents, there was certainly a good deal of intimidation

in some quarters of those who did not join the United Irishmen.

A JUDGEMENT: OR A ROMANCE WITH A TRAGIC ENDING

Mr. William Orr, of New Line, Saintfield, who believes he may be a

descendant of one of the parties involved in the burning of the McKee

family, has a quotation from "A History of the Descendants of David McKee,

Annahilt", published in Philadelphia in 1892. It includes the following

story about the Hugh McKee whose family suffered the terrible fate:

"Hugh was engaged to be married to a girl in the Ards. He went on the day

arranged to the tavern where according to Scottish fashion the marriage was

to take place. The clergyman, bridesmaid and all were there, except the

bride. After what seemed an endless wait and everyone had given up hopes of

the bride's appearance, Hugh, deeply chagrined and disappointed, turned to

the bridesmaid with the question "Will you have me, then?" She consented,

and the ceremony was immediately performed.

"The last word had scarcely been spoken, when the intended bride came

galloping up to the door on horseback, having been delayed by her

dressmaker. On learning the turn which matters had taken she violently

upbraided her friend and bridesmaid, and left, telling her that some

judgement would fall on her for what she had done.

"How tragic was the subsequent fate of Hugh, his wife, five sons and

three daughters, at their farmstead at Craigy. Dozens of Croppies attacked

the house with firearms. A valiant but ineffectual defence was offered. Soon

the house was ablaze, and in the end the inmates were immolated. The threat

of the disappointed bride was fearfully realised".

FROM THE ROBB MANUSCRIPTS

MR. COLIN JOHNSTON ROBB, of Magheratimpany, Ballynahinch, is well known

for his researches into local history, and his writings extend to several

volumes of manuscripts.

Mr. Robb kindly allowed us to study these and to use extracts from his

exhaustive accounts of events in County Down at the time of the '98

Rebellion.

The next few pages are condensed stories of Mr. Robb's writings.

BROTHERS IN BATTLE

Mr. Robb's great grandfather, James Robb, was a Yeomanry officer at the

Battle of Ballynahinch, while his (James's) brother, John, was one of the

rebel leaders, and there is a tradition that they met during the battle.

John was one of the `Fifty Pounders' who, because of the price on his

head, had to flee the country. He escaped to Norway where he later died.

In 1780 James Robb built the house at Magheratimpany in which Mr. C. J. Robb

now lives. The arms belonging to the local Yeomen were kept in the house and

the present dining room was known as "The Gun Room" in those days and indeed

up until the present century.

James was wounded during the battle and he received a drink in a house to

which he was carried unconscious. The drink revived him and after the battle

he called in the same house, and seeing the jug from which he drank, offered

to purchase it. The lady of the house gave it to him and he had an inscribed

metal plate attached to it. This is now in the possession of Mr. C. J. Robb.

YEOMAN'S SERVANT WAS REBEL

The Spa area was very divided in its loyalities in '98, and although

there was an efficient Yeomanry Corps under the command of James Robb

there was also a large number of United Irishmen.

These included not only James Robb's brother but also some of his

employees, including one, John Davey, who lived in a house now occupied by

Mr. Murphy, just a short distance from the Robb residence. Sensing that some

day he might be seeking a safe refuge, Davey prepared a specially

constructed turfstack with a hollow centre. After the battle, he escaped to

the home of his employer and hid in the stack while troops enjoyed the

hospitality of the loyal household.

CLOKEY OF SPA - "THE LAST OF THE REBELS"

The Clokey brothers from Spa were dedicated United Irishmen and were

among the officers who fought at the Battle of Ballynahinch.

The Robb writings include an old poem written by a John McMuIlan, a

native of Magheratimpany. It runs:

Did you hear of the Battle of Ballynahinch,

Where the country assembled in their own defence?

They assembled together and away they did go,

Led by their two heroes, Clokey and Munro."

The Clokey referred to was Andy Clokey, who resided on a farm now

occupied by Mr. Robert Watson, Ballymacarn. He was secretary of Spa

Volunteers and for a time was First Lieutenant of Volunteers. He was a

friend of Wolfe Tone, whom he met in his brother's house in Ballynahinch

when Tone was on a visit at one time to Lord Moira at Montalto. Clokey

escaped to America, but through the influence of his family with David Ker,

who prevailed upon the authorities, he was allowed to return home.

Clokey didn't rest immediately after the battle, because there is a on in

the Dunturk area that while being pursued by the Royalist Troops he doubled

back and attacked a band of horsemen in a field now owned by Mr. James

McKay.

Mr. Barney Milligan, of Dunturk, remembers old people discussing this

incident, and saying that the United men hid their saddles and bridles there

and continued to flee on foot, so that they could not be so easily traced.

"Clokey the last of the Rebels" was a familiar saying in the Spa area

until recent years, and it probably originated from the fact that Clokey

returned home in 1825 and lived to a good old age. By that time the

"Liberalism" of the area had almost disappeared and it later became a very

loyalist district.

COMMON GRAVE

There was also a common grave on the back road to Spa above the present

Croob Park housing estate in the woods near Spa Golf Course, where scores of

bodies were thrown after being taken there in block wheel cars. These were

pointed out to Mr. Robb by his grandfather, who died in 1912, and who had

known many descendants of those who fought in the battle.

RATHFRILAND AREA

The Rev. Samuel Barber, Minister of First Rathfriland Presbyterian Church

was involved with the United Irishmen. Rathfriland was by no means a

stronghold of United Irishmen. A few other rebels came from that district

including Tommy Cromie of Lisnacroppin, who was wounded in the Battle of

Ballynahinch, and was treated by a doctor in Kilkeel through which he passed

on his way to America. He was later pardoned and returned to Rathfriland and

lived with his son who was a shopkeeper in the town. Of course there was the

prominent United Irishman, Samuel Neilson (born 1761), son of Rev. Alex

Neilson, minister of Ballyroney Presbyterian Church.

A "LADY'S" ESCAPE

When the 22nd Light Dragoons and others were beating the country for

rebels who fled after the Battle of Ballynahinch, many rebels took refuge in

the islands of Strangford Lough and eluded arrest in this way.

John Torney, Hugh Coffey and Archie Murdock hid in an island at

Ballygagan Lake. Torney later made his way to the house of one Small and

dressed up in the clothes of Small's wife. Small took his horse from the

stable and rode off through Killyleagh with Torney riding pillion, no one

suspecting who the "lady" was. Torney escaped to America.

INCIDENT AT KILKEEL

It is sometimes wrongly supposed that only men from North Down were

involved with the United Irishmen.

This is probably because the majority of those at the Battle of

Ballynahinch were from North of the county, but the 'entire county was

involved in the movement and with the incidents which preceded the actual

Rising. For example, a particularly bloody incident occurred near Kilkeel in

1797 when between 10 and 20 innocent and helpless people were killed.

CATHOLICS PRESENT

It has been stated that there were no Roman Catholics present at the battle,

but Roger Magennis, a Catholic, in a letter dated 1805, states that his

corps, who were nearly all Catholics, held the offensive in the demesne

along the Ballynahinch River.

Capt. Hugh Jennings, also a Catholic, who was at one time Captain of the

Dunmore Yeomanry, was also present on the insurgent side with 450 Catholic

Citizen Soldiers. He escaped to America and then to France, where he joined

the French Army, and while serving in a volunteer company of the 8th French

Regiment of Light Infantry, he was killed at the Battle of Barossa, 5th

March, 1811.

ROADS TRENCHED

The roads were cut up or trenched from Saintfield to Ballynahinch in

order to make the approach of the military more difficult. This work was

carried out by Ballynahinch insurgents under a Moses Montgomery.

THE SAINTFIELD SKIRMISH

GRAVES AT YORK ISLAND

Saintfield, where traces of the liberation spirit which made it a strong

centre for United Irishmen in 1798 remained until recently, was the scene of

a skirmish on Saturday, 9th June, 1798 (see Chapter 31).

The military were defeated and the bodies of the dead Yorkshire Fencibles

were buried in what is known as York Island at the bottom of the First

Presbyterian Church Cemetery. Mr. Billy Grant, who is now in the R.U.C. and

whose parents reside at The Square, Saintfield, is one of the local people

to have found swords and bayonets in this swampy area.

In First Presbyterian Church itself there are several old weapons which

were reputed to have been used in the battle. They include firearms, swords

and a pike which was given to the late Rev. Stewart Dickson by Mr. Hugh

McWilliams, of Lessans, Saintfield.

KI LLINCHY MEN'S GRAVES

Two Killinchy men, who were involved in the Battle of Saintfield are also

buried at the bottom of the graveyard, and their graves are marked by

headstones.

The almost illegible inscriptions are -- `Here lies the remains of James

McEwen, Ballymacreely, Killinchy, who departed this life, 9th June, 1798,

aged 42 years.' (This was the date of the battle). `Here lies the body of

John Lowry, Ballymorran, Killinchy, died 19th June, 1798, aged 46.'

|